Master's Thesis

Utilizing Earth Systems Prediction Capability (ESPC) to Forecast Mistral Wind Events

Naval Postgraduate School — M.S. Meteorology and Physical Oceanography

Advisor: Dr. Wendell Nuss (NPS) | Co-Advisor: Dr. Carolyn Reynolds (NRL-MRY)

Abstract

Mistral wind events impact the coast of France and build seas in the Gulf of Lion. Strong and persistent wind events impact the routing of naval vessels and the ability to conduct operations in the Mediterranean. Properly identifying the meteorological synoptic picture is key to forecasters seeking to accurately predict Mistral events.

Navy Earth Systems Prediction Capability (ESPC) is a coupled model developed by Naval Research Laboratory to produce atmospheric, oceanographic, and ice sub-seasonal forecasts. Using publicly available deterministic forecasts (August 2017 through December 2021) and surface pressure and wind analyses, the skill of ESPC and forecaster thumb rules in predicting the Mistral between 7 and 21 days was evaluated.

Deterministic ESPC displays a low amount of skill in directly predicting Mistral events two to three weeks ahead. However, using ESPC predictions with forecaster thumb rules increased skill in some instances. Analysis of surface pressure and winds over the forecast area for the deterministic forecast was not found to be a reliable method for predicting events beyond the range of typical weather models.

Background

The Mistral is a strong, cold northwesterly wind that blows from southern France into the Gulf of Lion in the northwestern Mediterranean Sea. These katabatic wind events are driven by synoptic-scale pressure patterns and can persist from several hours to over a week. Mistral events occur frequently — roughly 7-15 times per month — generating gale to storm-force winds with rough to very rough seas.

The operational impacts on naval forces include reduced flight operations, challenging underway replenishment conditions, and hazardous sea states for small boat operations. Extended-range forecasting (7-21 days) of these events would significantly enhance operational planning capabilities for naval forces operating in the Mediterranean.

Methodology

- Analyzed publicly available deterministic ESPC forecasts from August 2017 through December 2021

- Used ECMWF ERA5 reanalysis data to verify historical Mistral events at NDBC 61002 (Lion Buoy)

- Applied forecaster thumb rules from Brody and Nestor (1980) for synoptic pattern recognition

- Evaluated surface pressure spreads at Perpignan, Marseille, and Nice

- Tested 850mb wind speed and direction rules at Nîmes

- Assessed 500mb winds at Brest and Bordeaux

- Verified forecast skill using 2x2 contingency tables (POD, FAR, CSI metrics)

How This Thesis Connects to My Work Today

This research asked a simple operational question: "Can we trust long‑lead forecasts for high‑impact wind events enough to plan real ship movements around them?"

Using the Navy's Earth Systems Prediction Capability (ESPC), I evaluated how well deterministic forecasts picked up Mistral wind events 7–21 days in advance and compared them with forecaster "thumb rules" and reanalysis data. The result: ESPC showed limited standalone skill, but combining model output with structured forecaster heuristics improved early warning in some scenarios.

This work sharpened how I think about:

- The limits of numerical models in complex regimes

- How to blend human expertise with imperfect data and models

- How bad assumptions in environmental input can quietly erode operational decisions

That same mindset now shapes my interest in validating environmental and EM inputs for autonomy, C5ISR, and EW systems operating in data‑sparse maritime environments.

Key Findings

⚠️ Important Context

Due to limitations of the IRI database, this study utilized single deterministic ESPC forecasts rather than the 16-member probabilistic ensemble the model was designed to produce. The ensemble only became operational in August 2020, providing insufficient data at the time of study. A probabilistic ensemble approach would likely demonstrate significantly improved skill over the deterministic results presented here.

Raw ESPC wind data at the Gulf of Lion buoy — not appreciably above the ~17% climatological rate

Skill decreases at longer lead times, reflecting increased atmospheric chaos in deterministic forecasts

Surface pressure spread (Perpignan, Marseille, Nice) and 850mb Nîmes wind rules showed POD gains above climatology

Improved detection came with high False Alarm Rate — ESPC shows high bias when using thumb rules but not raw data

What This Means in Practice

For operators and system designers, the takeaway is that long‑lead forecasts for high‑impact wind events can't be treated as plug‑and‑play truth. Raw model output alone added little skill beyond climatology, and useful early warning only emerged when we combined ESPC with structured forecaster heuristics—at the cost of higher false alarms.

Conclusions

There is not an appreciable amount of skill in the raw ESPC wind data at the Gulf of Lion buoy location beyond the ~17% climatological rate. When forecaster thumb rules from Brody and Nestor (1980) were applied, gains in POD above climatology were observed for the surface pressure spread at Perpignan, Marseille, and Nice, as well as the 850mb winds and intensity rules verified by ERA5 reanalysis. The 500mb winds at Brest and Bordeaux did not yield useful results.

The thumb rules that displayed utility also showed inherently high False Alarm Rates, suggesting ESPC has a high bias when using thumb rules but not when using raw model data. The deterministic model's portrayal of atmospheric chaos, especially at long lead times, meant the forecast was unable to capture the relative strength of pressure systems with enough accuracy to depict the synoptic picture that drove Mistral events.

Given these findings, forecasters would be best served by using the surface pressure spread for Perpignan, Marseille, and Nice or the Nîmes 850mb winds thumb rules rather than raw ESPC wind output—while accepting that high FAR should be expected. Probabilistic information from an ensemble would likely be more appropriate to use, and ensemble forecasts would be expected to show higher skill than a deterministic approach.

Results Visualizations

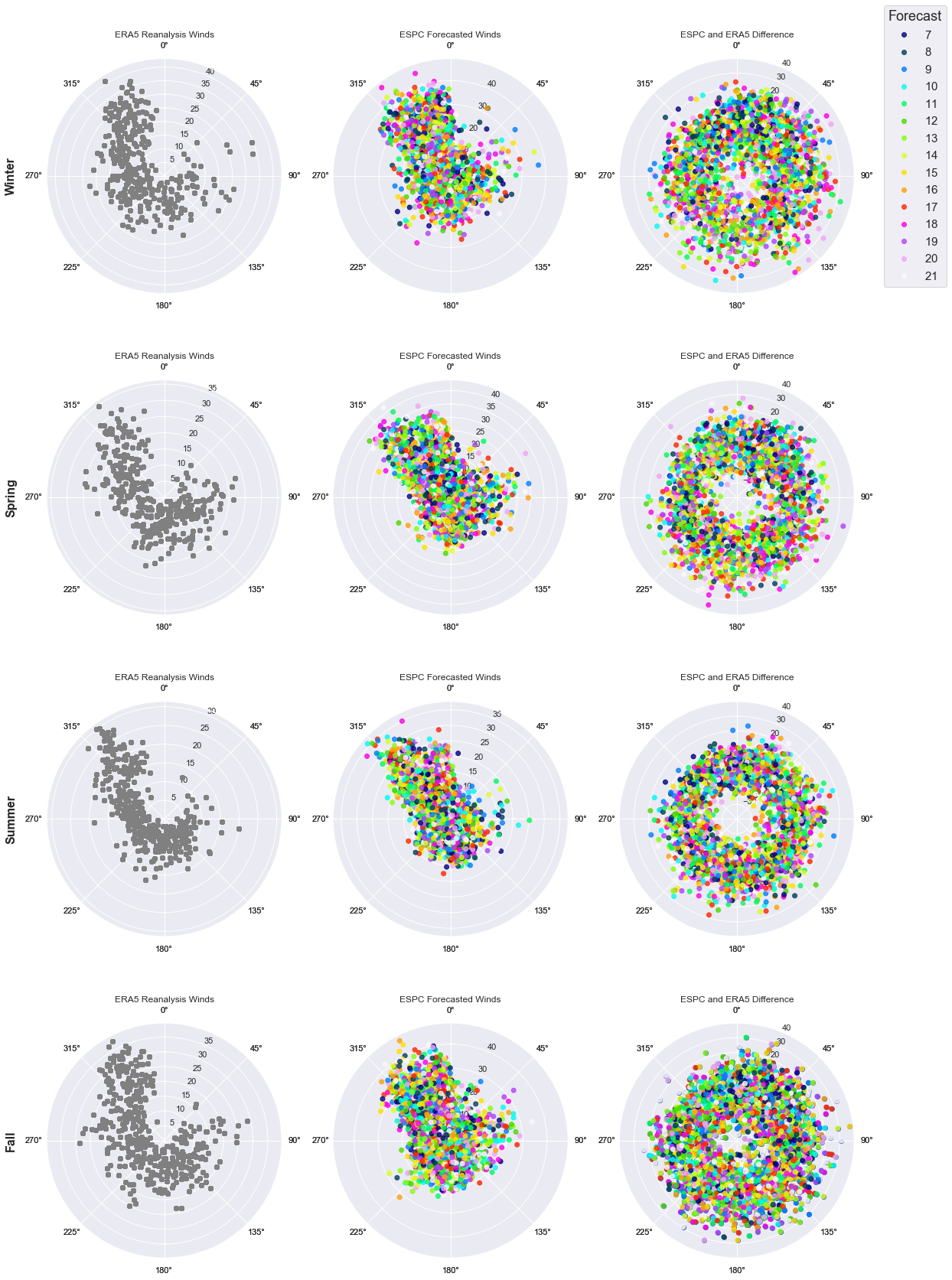

The wind rose plots below show why blindly trusting long‑lead model output is risky. ERA5 reanalysis (left column) captures the tight northwest clustering of true Mistral winds (~315°), while ESPC forecasts (middle column) scatter across many directions and speeds at 7–21 day lead times. The difference plots (right column) highlight how those errors grow with lead time—exactly the kind of hidden uncertainty that can quietly undermine routing, sortie, and replenishment decisions if it isn't understood and communicated.

Seasonal wind rose comparison showing ERA5 reanalysis winds (left), ESPC forecasted winds (center), and the difference (right). Colors indicate forecast lead time (days 7–21). Note the tight NW clustering in ERA5 versus the scattered ESPC predictions.

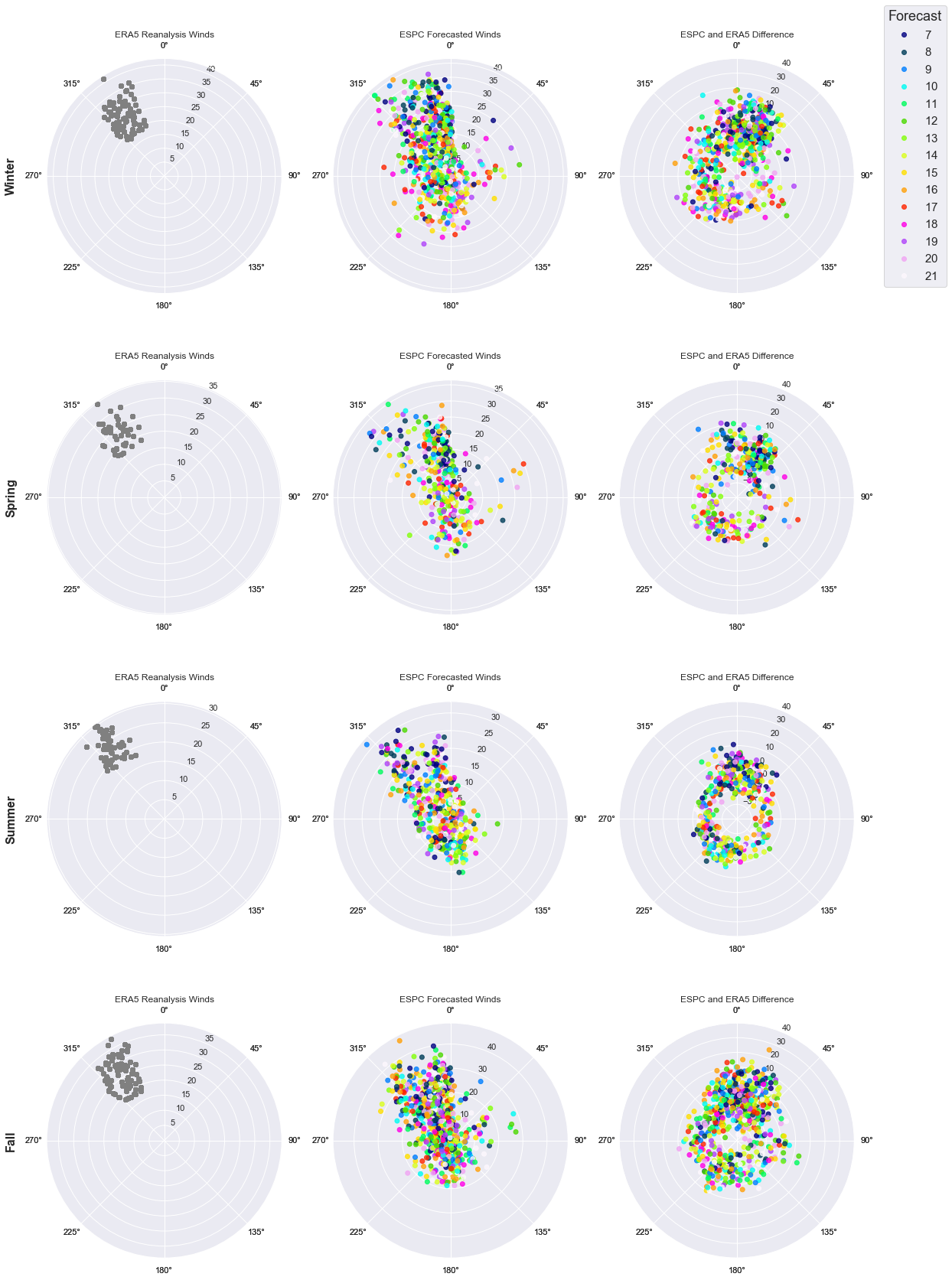

Same comparison, filtered to verified Mistral events. ERA5 winds show even tighter northwest clustering during real Mistrals, while ESPC forecasts remain scattered. For operators, this highlights that the deterministic model struggles to reliably flag high‑impact events at long lead times—critical context when using these forecasts for routing, sortie, or replenishment planning.

Operational Significance

This research provides operational forecasters with actionable guidance: when attempting to predict Mistral events in the 7-21 day window using deterministic ESPC output, thumb rules based on surface pressure spreads and 850mb winds offer more utility than raw model wind data — though confidence should be tempered by the expectation of false alarms.

The methodology developed — comparing raw model output against forecaster thumb rules using contingency table analysis — is directly applicable to other synoptic-scale wind events worldwide, including Tehuantepec gap winds and monsoonal flow patterns. This framework can help expand the utility of ESPC and other S2S (sub-seasonal to seasonal) forecasts for naval operational planning.

Future Work

- NAO Index Integration: Incorporate the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) index into ESPC‑based tools being developed by NRL. The relative strength of the Azores high is likely critical to Mistral likelihood and may be the missing metric that connects synoptic patterns to event probability.

- Ensemble Testing: Repeat this analysis with the full 16‑member probabilistic ensemble (operational since August 2020) to quantify how much skill gain we get over a single deterministic run and how that should change forecaster guidance.

- Expanded Thumb Rule Analysis: Extend the surface‑pressure‑spread and 850mb wind thumb‑rule approach to additional levels and locations to identify ridging/troughing signatures that improve early signal without exploding false alarms.

- Application to Other Wind Events: Apply the same raw‑model‑vs‑thumb‑rule comparison to other high‑impact wind regimes (e.g., monsoonal flow in Southeast Asia, gap winds in other straits) to build a reusable framework for operational S2S validation.